The public internet turned 25 today, which means it’s on its third unpaid internship, still living with its parents and has become a cynical nihilist with little hope for the future of humanity.

‘The Web took off without regard for borders at all’, said Tim Berners-Lee on the 25th anniversary of the idea for the Web’s conception in 2014. In fact, for the pioneers of the public internet, this liberation from state control (especially coming just after the end of the Cold War) was part of the great promise of the internet, a promise that it has not always been able to live up to.

Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.

— John Perry Barlow, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace” (1996)

Wikipedia still stands as one of the lasting legacies of this period of internet idealism, which seemed to fade in the wake of the Dot Com Bubble and the new political reality of a unipolar world order plagued by small wars and the fear of terrorism.

I think it’s worth repeating that out of the top 100 most popular websites in the world Wikipedia is the only one run by a charity. Its founding principle, to give everybody free access to the sum of all human knowledge, sounds idealistic to us now, it was only 15 years ago that the site was first created.

So can we still be optimistic about the internet given the problems it is plagued with and the negative impacts it has on many people’s lives? Absolutely, as Werner Herzog’s new film Lo and Behold: Reveries of the Connected World seems to suggest.

Herzog is a somewhat otherworldly figure, who delights in a kind of innocent awe at the possibilities of human potential. If you’ve not seen his film Cave of Forgotten Dreams, it is very good, and Lo and Behold seems to offer a kind of companion piece, juxtaposing the liminal nature of the Chauvet Cave paintings, the oldest extant human visual art in the world, with the bizarre Jungian subconscious which we have digitised in constructing the internet.

The New Statesman worries that Herzog is becoming a meme of himself, getting in the way of his subject matter. This cynicism seems to me reflective of the malaise with which we regard the internet now, with all its faults. People feel that we have lost something human by intertwining human destiny so closely with technology, and that is understandable, but feels like nostalgia to me. Herzog suggests in a Vice interview that we should think of the internet as we think of the Chauvet Cave paintings, not as something separate from our humanity, but as part of it, a representation of what is already inside of us.

So what does that make Wikipedia? Like the invention of writing, it takes the knowledge inside all of us and structures it, makes it editable, reviewable and verifiable. We are beginning to structure this knowledge in more and more complex ways that require huge amounts of data and processing power to create new tools which will allow us to better understand what we are, and how we can be better humans. In this respect, Wikidata holds great possibilities for the future analysis and structuring of knowledge. Who knows what kinds of technological or human progress it will allow us to make? It was impossible to see back when the first ARPANET intranet link was established in 1969.

“Kleinrock, a pioneering computer science professor at UCLA, and his small group of graduate students hoped to log onto the Stanford computer and try to send it some data. They would start by typing “login,” and seeing if the letters appeared on the far-off monitor.

“We set up a telephone connection between us and the guys at SRI …”, Kleinrock … said in an interview: “We typed the L and we asked on the phone,

“Do you see the L?”

“Yes, we see the L,” came the response.

We typed the O, and we asked, “Do you see the O.”

“Yes, we see the O.”

Then we typed the G, and the system crashed …

Yet a revolution had begun”“

It’s understandable why we are so cynical when we are constantly bombarded with terrible news, especially after the promise and potential which seemed to fill the 1990s with hope. Or perhaps it just felt that way because I was a child, who knows?

My most inspiring teacher at school once told me that the difference between being a sceptic and a cynic is that a cynic has already made their mind up. I think that this kind of cynicism is unhelpful, though probably inevitable at different points in history. For long periods of the Middle Ages, many people believed that the world had reached its final age and there were therefore few possible social or technological innovations worth striving towards. Then the Renaissance happened, which led to the Enlightenment and scientific revolution and here we are now.

Poststructuralist critic Frederick Jameson famously said in 2003 that “it has become easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”. This kind of thinking was also evident in Fukuyama’s ‘end of history’ hypothesis, that liberal capitalist democracy was the only political structure possible after the end of the Cold War. But this is just a lack of imagination, and we can do better. The internet is our imagination visualised, uploaded to the world’s networks, and we can query that imagination, we can use it as a repository to create new artworks and new ideas.

The internet is in a period of flux greater than ever before, as new digital communities come online, and we try to find a language for us all to communicate in. There are serious problems in making these systems work, but we have to resist cynicism and imagine how it could work and how amazing it could be if we are ever to achieve that potential greatness.

How did Werner Herzog learn to be a filmmaker? He read the entry for filmmaking in an encyclopedia and it told him everything he needed to get started.

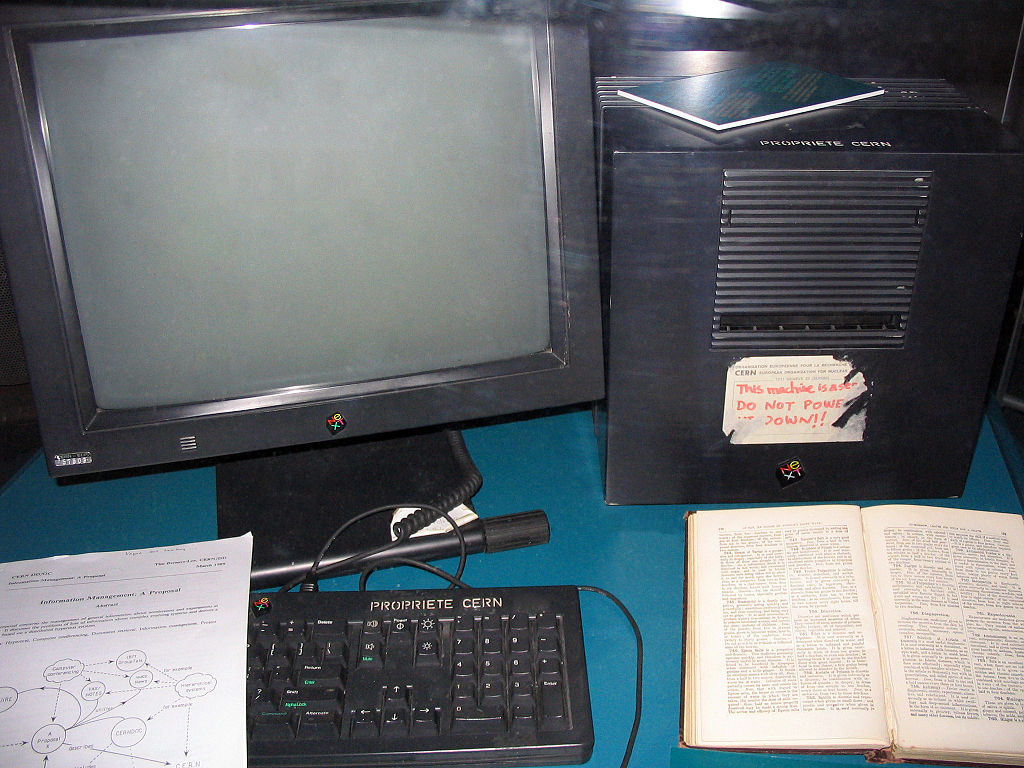

Credit on the Photo is wrong. [[:File:First Web Server.jpg]] is by [[User:Coolcaesar]]. Mine is [[:File:NeXTcube first webserver.JPG]]

Hi Geni, thanks for spotting that – the credit has now been corrected.